Rooftop solar alone will earn less under new California policy, but firms are developing programs to make it lucrative to add home batteries that help the grid.

California’s looming change to its net-metering regulations poses a severe threat to the growth of its rooftop-solar market. But it’s also likely to drive a big surge in installations of home batteries — and a stream of new opportunities for battery owners to participate in programs that pay them for helping to support the electric grid.

The California Public Utilities Commission is poised this week to adopt a new rooftop-solar policy that will encourage homeowners to add batteries alongside rooftop arrays, as we explained in part one of this series.

To understand the implications of this shift, let’s step back and look at the big picture. Rooftop-solar systems and California’s power grid are now closely intertwined. In the past, it might have made sense to consider rooftop solar in isolation from the grid because the arrays made up only a tiny fraction of the state’s overall energy mix. That’s no longer the case. California now has a huge amount of distributed solar — 12 gigawatts, equal to nearly one-quarter of the state’s peak electricity demand — and it will be getting a lot more.

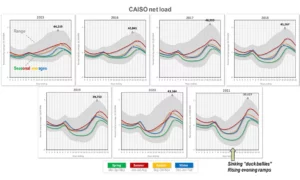

One result is that California often has more solar power than the grid needs when the sun is high, but then it doesn’t have enough clean power — or sometimes enough power of any kind — after the sun goes down. That grid dynamic is represented in the form of the “duck curve,” the name that state grid operator CAISO has given to the graph that shows how demand for grid electricity drops in the middle of the day as rooftop solar output is high and then ramps up when evening comes.

The following set of charts shows how the duck curve has become ever more duck-shaped over the past seven years, as more rooftop solar power has come on the grid. Each chart shows the average demand for grid electricity throughout the hours of an average day for a particular year, starting with 2015. California’s statewide grid supply-demand balance has been dramatically altered by rooftop solar, and the trends are only going to intensify as the state adds more solar power.

Adding more and more rooftop solar without batteries will further exaggerate the duck curve, leading to a steeper ramp-up in demand in the evenings. That’s why the CPUC’s pending plan will encourage customers to add batteries to rooftop solar systems, rewarding them for storing that excess solar power and discharging it when the grid needs it most, and slashing compensation for solar power exported to the grid at other times.

But the CPUC’s plan on its own isn’t enough to spur large numbers of homeowners to buy home batteries. The commission has merely outlined the future it wants to see; it’s now up to solar and battery installers to color in the picture. These companies are developing programs and systems that can capture the value that solar-plus-battery systems can provide to the grid, and make it enticing enough to lure new customers to invest.

Virtual power plants: The future of distributed solar and storage

One critical type of program that can harness solar-plus-storage systems to help the grid is a “virtual power plant.” By actively controlling the energy output from enough distributed household systems, it can mimic the operations of a power plant.

Take the example of sonnenConnect, a new virtual-power-plant program designed specifically for the California market. It’s a partnership between residential battery vendor sonnen, a Germany-based subsidiary of Shell that not only sells batteries but also controls them as grid assets, and Baker Electric Home Energy, the home-energy-services arm of Southern California electrical contractor Baker Electric. Baker Electric Home Energy has been installing rooftop solar for decades, as well as an increasing number of batteries alongside those solar systems over the past five years or so.

SonnenConnect is aimed at turning home batteries — which most customers see as an emergency backup power source — into a tool for making money by serving the grid in multiple ways, said Mike Teresso, president of Baker Electric Home Energy.

That starts with managing the charging and discharging of batteries to align with utility rate structures — limiting the use of grid power when it’s most expensive and maximizing the export of rooftop-solar power when it’s most valuable. Many Californians have already been doing this under the state’s existing net-metering system. After that system is replaced by the CPUC’s new regime, new owners of solar-plus-battery systems will have even more reason to be strategic in deploying their batteries. “A lot of this is wrapped up in wherever net metering is going,” Teresso said.

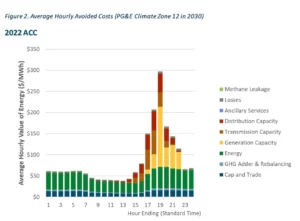

Right now, the CPUC’s proposed structure for buying power that home solar-plus-battery systems export to the grid offers one clear signal: Systems should store up solar power during the day and discharge it during the few hours, usually on summer evenings, when it’s far more valuable than at any other time. The chart below shows an example of how significantly the value of power could vary throughout the day (under the CPUC’s plan, rooftop solar exported to the grid will be valued according to the grid costs it helps to avoid).

But there are more opportunities to use virtual power plants to provide grid services, said Blake Richetta, CEO of sonnen’s U.S. business. The partners behind sonnenConnect see enough value that they’re offering $750 rebates to customers who sign up for the program.

Sonnen can use its virtual power plant to participate in a number of demand-response programs, including some that the CPUC has created in the past two years to combat the rising threat of grid shortfalls on summer evenings. Those programs have been generating enough money to enable sonnen to send customers monthly checks ranging from a few dollars up to $70, he said.

This is far from a unique concept. In Germany, sonnen has operated a network of solar-and-battery-equipped homes for years. In California, solar and battery vendors including Sunrun, Tesla and Sunnova have signed customers up to participate in virtual power plants that played a role in reducing grid stress during heat-wave-driven energy shortages in 2020 and in September of this year, helping to keep the shaky grid running.

The California Solar and Storage Association estimates that the more than 81,000 batteries connected to home solar systems in California as of this fall add up to nearly 900 megawatts of potential grid aid. In the future, the opportunities for actively managing these aggregations of solar-battery systems to make money is sure to expand, Richetta said.

Importantly, these money-earning opportunities for customers, installers, battery vendors and virtual-power-plant operators reflect the value that they’re providing to the grid and to society at large, he said. More energy being sent from homes to the grid when it’s under peak stress means less fossil-fueled power being dispatched to fill those gaps, and potentially less money spent on expanding the power grid to bring energy from far-off wind and solar farms or from resources in other states.

Whether or not the CPUC’s replacement for net metering properly incentivizes all these activities is out of sonnen’s control, Richetta said. Much of the potential for distributed solar and batteries to cost-effectively serve grid needs relies on a healthy and growing underlying market for those technologies. But it’s also clear that the rooftop solar industry in California “cannot be dependent on net metering,” he said. “You have to have a broader framework.”

Getting granular with grid value

Sonnen’s virtual-power-plant activities are largely targeted at the wholesale energy market today. But there are opportunities to use virtual power plants in more geographically targeted ways. California’s grid is a highly complex and segmented network with different needs in different places.

Large-scale central generators power high-voltage transmission lines that carry electricity to substations scattered across the state. Those substations convert that power to lower voltages; it’s then carried across distribution grid networks and feeder lines to end customers. All of these nodes on the network face their own particular challenges — and distributed solar and batteries connected at the very edges of those dispersed networks may be well positioned to solve problems in a particular location that can’t easily be solved in other ways.

Carla Peterman, chief sustainability officer at utility Pacific Gas & Electric, highlighted this localized value during oral arguments on the CPUC’s net-metering proposal last month. “If we want to have true grid benefits, we have to make sure we’re getting the right pricing signals and that we’re targeting areas where there are capacity constraints,” she said.

Making solar-plus-battery systems an integral part of the grid

Distributed solar and batteries can do more for utilities than decrease peak demand and defer grid upgrades. California has a growing roster of projects that have enlisted distributed energy resources to mitigate the need for large-scale investments.

Back in 2014, utility Southern California Edison contracted for more than 250 megawatts of distributed solar, batteries and other forms of “behind-the-meter” resources to help manage the complex stresses caused by the closure of the San Onofre nuclear power plant. A similar round of contracts paid for batteries, smart thermostats and other resources to reduce strain on the region’s power supply caused by the partial shutdown of the Aliso Canyon fossil-gas storage facility in 2016.

Distributed energy has also been enlisted to eliminate the need for building or expanding fossil-fired power plants in Central and Northern California. While large-scale batteries have been the primary resource tapped for these needs, pockets of residential solar-battery systems are also playing a role, with companies like Sunrun and virtual-power-plant startup Swell signing up customers who agree to turn over control of their batteries during certain hours of the year in exchange for cheaper installations or recurring payments.

The opportunities for these types of virtual-power-plant contracts to earn stable and predictable revenue for meeting grid needs are growing across California, said Swell CEO Suleman Khan. His company has targeted several such opportunities in the state, including projects linked to solving the grid needs caused by the aforementioned shutdowns of the San Onofre nuclear plant and Aliso Canyon gas storage site.

Much of the focus on solar-plus-battery virtual power plants in California thus far has been on the role they played in easing grid strain during the state’s grid emergencies. California regulators and policymakers have approved billions of dollars of grid-reliability spending to manage the rising risks of supply shortages and rolling blackouts during these emergencies.

But Khan pointed out that the projects Swell is doing in Southern California are valuable far more often than during emergencies. “They’re intended to be used 90 to 120 times per year, essentially bringing down load in a permanent manner,” he said.

And conveniently enough, the times when Swell’s customers are being asked to allow their batteries to be tapped for more targeted grid relief tend to coincide with the hours of the day when the CPUC’s proposed new rooftop-solar structure will most richly reward customers for the power they send back to the grid. If those values can be aligned in ways that earn customers a significant revenue stream, “then all of a sudden a battery doesn’t seem that expensive,” he said.

It’s important to highlight that these opportunities aren’t equally available to utility customers across California, however. Not everyone lives in a neighborhood that’s powered by grid infrastructure that could benefit from deferred investment or in a region that’s being targeted by these utility programs.

And, of course, not everyone can install solar and battery systems. Many Californians aren’t wealthy enough to buy such systems outright or lack the credit ratings to secure financing for them. Many more rent their homes or live in apartment buildings or condominiums. The issue of equitable access to solar and batteries is what we’ll explore in the last installment of this three-part series on California’s post-net-metering future.